I dared not go below, I dared not leave the helm so here all night I stayed, and in the dimness of the night I saw it - Him! God forgive me, but the mate was right to jump overboard. It is better to die like a man; to die like a sailor in the blue water no man can object. But I am captain, and I must not leave my ship. But I shall baffle this fiend or monster, for I shall tie my hands to the wheel when my strength begins to fail, and along with them I shall tie that which He - it! - dare not touch; and then, come good wind or foul, I shall save my soul, and my honour as a captain.

On the 24th October 1885 the town of Whitby bore witness to an incident that would later become the basis for one of the most famous shipwrecks in the history of literature.

The following extract is taken from an article that appeared in the Whitby Gazette on the 31st October 1885.

A little later in the afternoon a schooner was descried to the south of the harbour, outside the rocks. Her position was one of great danger; for being evidently unable to beat off, there seemed nothing for it but to be driven among the huge breakers on the scar. Her commander was apparently a man well acquainted with his profession, for with consummate skill he steered his trim little craft before the wind, crossing the rocks by what is known as the ’sledway’ and bringing her in a good position for the harbour mouth.

The piers and the cliffs were thronged with expectant people, and the lifeboat ‘Harriot Forteath’ was got ready for use in case the craft should miss the entrance to the harbour and be driven on shore. When a few hundred yards from the piers she was knocked about considerably by the heavy seas, but on crossing the bar the sea calmed a little and she sailed into smooth water. A cheer broke from the spectators on the pier when they saw her in safety.

Two pilots were in waiting, and at once gave instruction to those on board, but meanwhile the captain not realising the necessity of keeping on her steerage, allowed her to fall off and lowered sail, thus causing the vessel to swing towards the sand on the east side of the harbour. On seeing this danger the anchor was dropped, but they found no hold and she drifted into Collier’s Hope and struck the ground. She purported to be the schooner ’Dmitry’ of Narva, Russia, Captain Sikki, with a crew of seven hands, ballasted with silver sand. During the night of Saturday the men worked incessantly upon her that her masts went by the board and on Sunday morning, she lay high and dry a broken and complete wreck, firmly embedded in the sand.

The connection between the Irish author Bram Stoker and Whitby are very well documented, it is also well known that the wrecking of the Russian schooner the ‘Dmitry’ inspired Stoker to create one of the most memorable scenes in Dracula - the arrival of the Count in England.

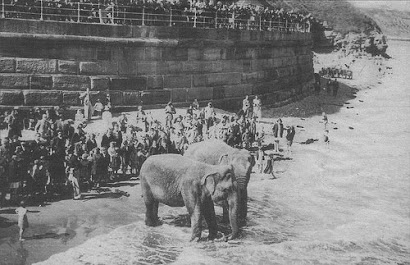

|

| The wreck of the Dmitry (Frank meadow Sutcliffe) |

…leaping from wave to wave as it rushed as headlong speed, swept the strange schooner before the blast, with all sail set, and gained the safety of the harbour. The search light followed her, and a shudder ran through all who saw her, for lashed to the helm was a corpse, with drooping head, which swung horribly to and fro at each motion of the ship. No other form could be seen on deck at all. A great awe came on all as they realised that the ship, as if by a miracle, had found the harbour, unsteered save by the hand of a dead man! However, all took place more quickly than it takes to write these words. The schooner paused not, but rushed across the harbour, pitched herself on that accumulation of sand and gravel washed by many tides and many storms into the south-east corner of the pier jutting under the East Cliff, known locally as Tate Hill Pier.

|

| The Flag of Distress: The brig Mary and Agnes (Frank Meadow Sutcliffe) |

passage taken from the same Gazette article dated 31st October 1885 illustrates.

In the mean while the lifesaving brigade by a well directed rocket threw a line over the brigantine which now was seen to be the Mary and Agnes, of Scarborough. It seemed a long time before the crew on board fixed the apparatus, but eventually this was done, and the youngest of them, a lad of about fifteen years, was sent ashore in the breeches. In being dragged towards the shore the poor little fellow was struck by many seas and considerably buffeted about. There were, however, many ready and willing among those on shore to rush into the water and bring him to land.

What makes this day’s events all the more dramatic is that both shipwrecks were captured on camera by the famous Victorian photographer Frank Meadow Sutcliffe.

No comments:

Post a Comment