Sound recordist Craig Vear has made a sound poem of the River Esk which has been released on CD by 3Leaves. This is the review I did of the work, which was originally published in The Field Reporter blog earlier this year.

What does a river mean?

In some cases it means an obstacle, a barrier that needs to be bridged. For wildlife it means a range of habitats, both beneath the water and along the banks. A river geographically connects the towns and villages along its course. Rivers are often pressed into service as metaphors for life. They begin as unruly infants, high up in the hills, full of energy and exhuberance. Over time and distance they become languid and peaceful before finally opening out into the unforgiving sea.

Rivers have a multitude of meanings and can be read in many ways. Craig Vear’s sound poem Esk is a portrait of a 28 mile long English river flowing from its birthplace on the hills at Westerdale, through the North Yorkshire Moors National Park, and into the North Sea at the town of Whitby. Vear has produced a piece of work that is rich in detail and yet not cluttered or contrived. As with any portrait, a true appreciation of character emerges the longer and deeper you look.

Curiously Vear collected the raw materials for Esk by beginning at the outer harbour wall at Whitby, then moving upriver towards the source. After acquiring what must have been hours of recordings, the piece was then edited and composed in the order of the Esk’s actual flow. In other words in the opposite direction to which it was recorded. In a sense it is moving backwards in time as it gets closer to the sea. The seasons flow in reverse, proving that sound art can render time plastic.

Recording the flow of water in all its various forms is one thing, but what really defines a river is its banks. They channel it and give it form. The geographical nature of the countryside it passes through and the life around it imbue a unique personality. At various points along the route we hear the engines of vehicles crossing bridges spanning the water, and occasionally human voices. This work shouldn’t be taken as an idealised, pastoral portrait. It is grounded in reality and there are some surprisingly jarring sound events. Rough edges have not been smoothed off.

At several points we are plunged beneath the surface into the world of crayfish, dragonfly nymphs and trout. Hydrophone recordings always feel like eavesdropping on sounds that we as air-listeners weren’t designed to hear. They always take us into an unknowable place. We can picture the silver surface of the water undulating above us and the stone strewn bed beneath us.

There are many different facets to Esk, and it moves quickly between environments. On the moors insects buzz, in the trees birds call and in the fields cattle low balefully. We move on towards the sea, the natural direction of flow giving this work its linearity and purpose. The final sounds are deep water surges showing that the journey is complete and the Esk has been reclaimed by the sea.

As with all 3Leaves releases, Esk comes exquisitely packaged in a postcard sized cover depicting the river in winter. Snowblown trees and white banks speak equally of picturesque stillness and the harshness of nature. A fitting image.

What does a river mean?

According to Heraclitus it means change. In his words; ‘You can never step into the same river; for new waters are always flowing on to you’. Similarly, every time you listen to this piece by Craig Vear, expect something different being carried on the current.

3Leaves website

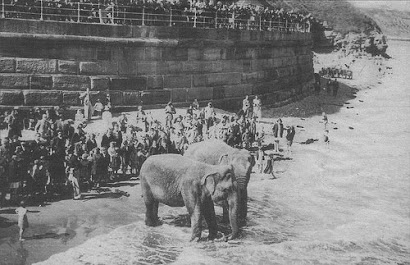

ELEPHANTS ON WHITBY BEACH

Saturday, 14 April 2012

Monday, 2 April 2012

WADE'S STONES

There are two Wade's Stones still standing, one at East Barnby and one near Goldsborough. They are thought to be prehistoric in origin and the southern stone (East Barnby) has been associated with an Anglo Saxon inhumation. A spearhead has also been found there (Frank Elgee, Early Man on the North Yorks Moors, 1930).

Although only two remain today, it is claimed that there were at least four stones in the past. When the Reverend George Young spoke about them in his History of Whitby of 1817, he described the sites thus: 'A stone above East Barnby, which once had another near it, is said to mark out the grave of a giant called Wade; but that honour is assigned, by another tradition, to two similar pillars near Goldsborough, standing about 100 feet asunder'.

Sometime between February and March 2008 the East Barnby stone toppled over, probably due to centuries of cultivation around its base. However Tees Archaeology have recently erected it again. Both stones stand on working farms on agricultural land.

The question of how the character Wade became so closely associated with this area is another story altogether. An interesting accountof Wade and his origins, beginning with the story of what occurred when the author Mike Haigh visited one of the sites, can be found here.

Although only two remain today, it is claimed that there were at least four stones in the past. When the Reverend George Young spoke about them in his History of Whitby of 1817, he described the sites thus: 'A stone above East Barnby, which once had another near it, is said to mark out the grave of a giant called Wade; but that honour is assigned, by another tradition, to two similar pillars near Goldsborough, standing about 100 feet asunder'.

|

| Two views of Wade's Stone (south) at Goldsborough |

|

| The fallen Wade's Stone (South) at East Barnby Photo by David Raven 28.03.2008 |

|

| As the stone appears today, thanks to the efforts of Tees Archaeology |

Saturday, 24 March 2012

JRR TOLKIEN

...

It is also interesting to note Tolkien’s handwriting even at this early age has taken on the appearance of the unique Elvish style that he incorporated in to all his Middle Earth his works.

His second visit appears to be in the early part of 1955, and judging by a correspondence sent from Oxford to a Mrs Turnbull of Whitby he was on the cusp of a momentous occasion.

In the letter Tolkien thanks Mrs Turnbull for her ‘munificent and magnificent gift’ (apparently champagne), he then apologies for his tardy response - the gift having only arrived two days before, and finally goes on to discuss the cause for his celebrations - clearing his desk of The Return Of The King:-

'Though sending off the last items (with a marginal comment 'and at last') for Vol III might have seemed a suitable occasion for the withdrawing of at least one cork, I have so far refrained; but when I drink I shall remember with a gratitude at least as warm and deep as Old Rory felt for the bottles of Old Winyards. I can only hope Vol III will be up to it!'

Although only speculation on my part it would be nice to think that the town of Whitby and the ancient landscape that surrounds it may have - to a very small degree - helped to shape two of the greatest works of fiction ever imagined.

Post by Richard Locker

JRR Tolkien made two visit to the town of Whitby in his lifetime, the first was in the summer of 1910 as an 18 year old student of King Edward’s School in Birmingham.

Always a keen artist it was whilst holidaying in the town that he sketched ‘The Ruins Of The West End Of The Abbey’, a picture that hints at his broadening artistic ability; a skill which would eventually be used to great effect in illustrating his books The Hobbit and The Lord Of The Rings.

His second visit appears to be in the early part of 1955, and judging by a correspondence sent from Oxford to a Mrs Turnbull of Whitby he was on the cusp of a momentous occasion.

In the letter Tolkien thanks Mrs Turnbull for her ‘munificent and magnificent gift’ (apparently champagne), he then apologies for his tardy response - the gift having only arrived two days before, and finally goes on to discuss the cause for his celebrations - clearing his desk of The Return Of The King:-

'Though sending off the last items (with a marginal comment 'and at last') for Vol III might have seemed a suitable occasion for the withdrawing of at least one cork, I have so far refrained; but when I drink I shall remember with a gratitude at least as warm and deep as Old Rory felt for the bottles of Old Winyards. I can only hope Vol III will be up to it!'

Although only speculation on my part it would be nice to think that the town of Whitby and the ancient landscape that surrounds it may have - to a very small degree - helped to shape two of the greatest works of fiction ever imagined.

Post by Richard Locker

Wednesday, 21 March 2012

ADDERS EMERGING FROM HIBERNATION

21st March 2012

Adders emerging from hibernation on the North Yorkshire Moors near Goathland. This photo was taken by Andy Cook during a morning walk.

Adders emerging from hibernation on the North Yorkshire Moors near Goathland. This photo was taken by Andy Cook during a morning walk.

THE DANZIG

The cruisers of the Bremen class consisted of seven ships in all. Apart from one (The Lübeck, which had a turbine engine) they all relied on triple expansion engines. They were manouverable vessels, but notorious for rolling badly when the seas became stormy. All were named after German towns.

Even at the start of World War I they were not modern ships and several were lost. Nevertheless some survived throughout World War II, although not as combat vessels.

Prior to World War I the small cruiser Danzig was utilised in fleet operations and in artillery training. In 1914 she was once again used in fleet operations. She took part in the battle of Helgoland and was involved in operations at the Baltic Islands.

In 1919 the Danzig was delivered to England to be scrapped. This photograph shows her in Whitby harbour at the end of her final voyage. She was dismantled between 1922-1923.

Even at the start of World War I they were not modern ships and several were lost. Nevertheless some survived throughout World War II, although not as combat vessels.

Prior to World War I the small cruiser Danzig was utilised in fleet operations and in artillery training. In 1914 she was once again used in fleet operations. She took part in the battle of Helgoland and was involved in operations at the Baltic Islands.

In 1919 the Danzig was delivered to England to be scrapped. This photograph shows her in Whitby harbour at the end of her final voyage. She was dismantled between 1922-1923.

Tuesday, 20 March 2012

THE PLAGUE BIBLE

During the 18th century the Quarantine or Plague Bible was commonly used in England as the first measure of defence against the deadly and highly contagious disease The Plague.

During the 18th century the Quarantine or Plague Bible was commonly used in England as the first measure of defence against the deadly and highly contagious disease The Plague. The first Act of Quarantine was not officially established in England until 1710, some forty years after the country had last suffered at the hands of the Plague. The act itself would undergo several further amendments throughout the 1700’s, each one becoming progressively more stringent. Until eventually in 1824 the laws were finally relaxed, making the act of quarantine only at the discretion of the privy council.

Up to this point a ship suspected of carrying the plague was placed in isolation for forty days at a distance of up to three miles off shore. The problem with this was that the Master of the quarantined vessel had to then present a report to the local port authority within the first 24 hours, which meant that at some point the Customs Official dealing with the case would have to come into physical contact with the ship’s crew, leading to the possibility that he could catch the disease himself.

So to resolve this problem the Plague Bible was introduced and Whitby, like all major sea ports that dealt with imported goods, immediately began using this rather simplistic and very honest method as a means of verifying whether it was necessary to quarantine a ship or not.

A Boarding Officer (tide surveyor) and a tide-waiter plus a crew of six would use a purpose built coble - a small locally built fishing boat - to a approach the quarantined vessel. Making sure that they were to the windward side of the ship, the Boarding Officer would then hail the ship’s Master.

Then, using a boat hook to hold up a metal encased copy of the New Testament, the Customs Official would make the Master swear an oath upon the Bible that neither he nor any member of the crew needed quarantine. On assuming that the ship’s Master was a Christian, and also that he was actually telling the truth, the vessel was then deemed safe enough to board.

It is also worth noting that in some sea ports across England a copper encased Bible would be fixed to a line and passed over to the quarantined vessel. Once the ship’s Master had sworn his oath, the Bible was cast overboard and dragged back through the sea to the official’s boat, a process which was believed to cleanse the book of any disease and impurities it might be carrying.

Sunday, 27 November 2011

LIONEL CHARLTON AND HIS HISTORY OF WHITBY 1779

After a classical education at the University of Edinburgh, Lionel Charlton settled in Whitby around the year 1748. He was a lame man with a withered hand, yet these obstacles did not prevent him from setting up a school which was for many years the principal one in Whitby.

After a classical education at the University of Edinburgh, Lionel Charlton settled in Whitby around the year 1748. He was a lame man with a withered hand, yet these obstacles did not prevent him from setting up a school which was for many years the principal one in Whitby.Considered by many a strict schoolmaster, he was nevertheless a man of great integrity and would not accept anything other than his agreed salary from his employers. He was stubborn in attitude and never surrendered his point of view in an argument.

Around 1762 Charlton published a paper claiming that extracting money from the local fishermen in taxes known as tithes was unjust. Dr. Hayter, Bishop of Norwich, was in charge of this process, and he felt this paper reflected badly on his character, especially as Charlton seemingly pulled no punches whilst voicing his opinion of the Bishop.

|

| The South East Prospect of Whitby Abbey 1773 |

Dr. Hayter threatened to prosecute Charlton unless he retracted his 'obnoxious expressions'. True to his character Charlton refused point blank, immediately putting his career, the safety of his family and his financial security in peril. This incident may well have ruined the dogmatic schoolmaster had the Bishop not died , putting a stop to the prosecution.

Toward the end of his life, after a long acquaintance with the town, Lionel Charlton undertook the writing of his History of Whitby. Having his employer Mr Cholmley's library at his disposal and access to the records of the Abbey, several years were spent in research.

|

| The title page and the canvas map |

This First Edition contained a canvas fold out map of Whitby which was reprinted by Young in his history of the town in 1817. Charlton's book is not an easy read. It is arranged chronologically, therefore subjects are not gathered together, but occur piecemeal throughout the work. It contains a huge amount of charters and exhibits 'a greater display of laborious research than of solid judgement'.

Many thanks to Mr Stephen Boddy for lending me his precious first edition of this book

Thursday, 10 November 2011

ABSOLUTE ZERO

This is a slightly unusual post from OUT ON YE! as it is music related, but it is also kind of literature related (in the widest sense) so I thought this might be the place to publish it.

Long thought lost to the world (and some would say for the better) I came across this fanzine dedicated to the Whitby music scene. It came out in 1987, and I clearly remember pounding away on an old typewriter deep into the early hours of the morning producing it.

It ran for two issues, and this premiere publication includes interviews with M.O.D., Sons of Gods Mate, live reviews of the likes of Indian Dream and Chumbawamba, a cartoon or two and a Wilfred Owen poem to round things off.

Click on the images for a readable version.

Sunday, 6 November 2011

LEECH ON THE BEACH

On the 24th of September this year we were down by the beach when my five year old daughter Iris came up from the sand clutching something in her hand. It looked like a curled up worm with a flattened body, and I couldn't recognise it as one of the creatures normally found on the shore.

Placing it in a paper cup of sea water, it stretched out and fixed one end of its body to the side of the cup with a sucker. It was clearly a leech. After taking a few photographs for identification purposes, the leech was placed in a pool under some rocks so it could crawl away from predatory seagulls until the tide came in.

At home, despite consulting numerous identification guides I couldn't find a match. Marine leeches prey on fish and are usually found attached to them when they are caught. It didn't look like a marine leech.

The photos were posted on the Wild About Britain water life forum and It's fair to say they caused much consternation. Someone even suggested that it might be a juvenile hagfish (a jawless fish similar to a lamprey). Of course the sucker and highly extendable body precluded this. It was certainly a member of the Hirudinea, the leech family.

There are lots of pipes that drain water from the cliffs onto the beach just below where our beach hut is situated, and it struck me that this might not be a marine species at all, but a fresh water or terrestrial creature that had been washed out of one of these ducts. Indeed the most likely ID turned out to be the rare terrestrial leech Trocheta subviridis.

Quite capable of living in water with a high level of pollution from sewerage, the leech was undoubtedly living in one of the drainage pipes and was flushed out onto the sand. Trocheta subviridis is a predator of earthworms and leaves the water to hunt. There are reports of it crawling up plugholes into people's sinks and it is sometimes dug up in gardens. Because of its lifestyle it is sometimes called the Amphibious Leech.

In the journal Parasitology, vol. III, p. 182 ther is an account of one being found on an allotment in 1922.

In April of this year a specimen was sent to the Agricultural Department, Armstrong College, by Mr S. Giles of South Shields, along with a note explaining that it had been found “down in the first spit of the soil” in one of a group of allotments there. It was obviously a specimen of a leech, but the specimen was submitted later, to Mr John Ritchie, the Museum, Perth, who kindly identified the species as Trocheta subviridis, and who mentioned that "this gives so far as I am aware, a more northern habitat than hitherto recorded".

Definitive identification of leeches needs to be carried out when the creature is still alive and its body relatively transparent. Also a handlens is essential to count eye spots. This has been a lesson to me. Now whenever I go to the beach, I always take a magnifying glass of some sort. You never know what you might find.

Placing it in a paper cup of sea water, it stretched out and fixed one end of its body to the side of the cup with a sucker. It was clearly a leech. After taking a few photographs for identification purposes, the leech was placed in a pool under some rocks so it could crawl away from predatory seagulls until the tide came in.

At home, despite consulting numerous identification guides I couldn't find a match. Marine leeches prey on fish and are usually found attached to them when they are caught. It didn't look like a marine leech.

The photos were posted on the Wild About Britain water life forum and It's fair to say they caused much consternation. Someone even suggested that it might be a juvenile hagfish (a jawless fish similar to a lamprey). Of course the sucker and highly extendable body precluded this. It was certainly a member of the Hirudinea, the leech family.

There are lots of pipes that drain water from the cliffs onto the beach just below where our beach hut is situated, and it struck me that this might not be a marine species at all, but a fresh water or terrestrial creature that had been washed out of one of these ducts. Indeed the most likely ID turned out to be the rare terrestrial leech Trocheta subviridis.

Quite capable of living in water with a high level of pollution from sewerage, the leech was undoubtedly living in one of the drainage pipes and was flushed out onto the sand. Trocheta subviridis is a predator of earthworms and leaves the water to hunt. There are reports of it crawling up plugholes into people's sinks and it is sometimes dug up in gardens. Because of its lifestyle it is sometimes called the Amphibious Leech.

In the journal Parasitology, vol. III, p. 182 ther is an account of one being found on an allotment in 1922.

In April of this year a specimen was sent to the Agricultural Department, Armstrong College, by Mr S. Giles of South Shields, along with a note explaining that it had been found “down in the first spit of the soil” in one of a group of allotments there. It was obviously a specimen of a leech, but the specimen was submitted later, to Mr John Ritchie, the Museum, Perth, who kindly identified the species as Trocheta subviridis, and who mentioned that "this gives so far as I am aware, a more northern habitat than hitherto recorded".

Definitive identification of leeches needs to be carried out when the creature is still alive and its body relatively transparent. Also a handlens is essential to count eye spots. This has been a lesson to me. Now whenever I go to the beach, I always take a magnifying glass of some sort. You never know what you might find.

Sunday, 16 October 2011

A TALE OF TWO WRECKS

By Richard Locker

I dared not go below, I dared not leave the helm so here all night I stayed, and in the dimness of the night I saw it - Him! God forgive me, but the mate was right to jump overboard. It is better to die like a man; to die like a sailor in the blue water no man can object. But I am captain, and I must not leave my ship. But I shall baffle this fiend or monster, for I shall tie my hands to the wheel when my strength begins to fail, and along with them I shall tie that which He - it! - dare not touch; and then, come good wind or foul, I shall save my soul, and my honour as a captain.

Taken from the log of the ‘Demeter’ (Varna to Whitby)

The following extract is taken from an article that appeared in the Whitby Gazette on the 31st October 1885.

A little later in the afternoon a schooner was descried to the south of the harbour, outside the rocks. Her position was one of great danger; for being evidently unable to beat off, there seemed nothing for it but to be driven among the huge breakers on the scar. Her commander was apparently a man well acquainted with his profession, for with consummate skill he steered his trim little craft before the wind, crossing the rocks by what is known as the ’sledway’ and bringing her in a good position for the harbour mouth.

The piers and the cliffs were thronged with expectant people, and the lifeboat ‘Harriot Forteath’ was got ready for use in case the craft should miss the entrance to the harbour and be driven on shore. When a few hundred yards from the piers she was knocked about considerably by the heavy seas, but on crossing the bar the sea calmed a little and she sailed into smooth water. A cheer broke from the spectators on the pier when they saw her in safety.

The Dmitry was not the only vessel to come to grief at Whitby on the 24th October, earlier in the day a Scarborough brig named Mary and Agnes was pounded ashore whilst sailing from Newcastle to London with a cargo of scrap iron. This incident appeared to be even more dramatic than that of the Dmitry as this

passage taken from the same Gazette article dated 31st October 1885 illustrates.

In the mean while the lifesaving brigade by a well directed rocket threw a line over the brigantine which now was seen to be the Mary and Agnes, of Scarborough. It seemed a long time before the crew on board fixed the apparatus, but eventually this was done, and the youngest of them, a lad of about fifteen years, was sent ashore in the breeches. In being dragged towards the shore the poor little fellow was struck by many seas and considerably buffeted about. There were, however, many ready and willing among those on shore to rush into the water and bring him to land.

What makes this day’s events all the more dramatic is that both shipwrecks were captured on camera by the famous Victorian photographer Frank Meadow Sutcliffe.

I dared not go below, I dared not leave the helm so here all night I stayed, and in the dimness of the night I saw it - Him! God forgive me, but the mate was right to jump overboard. It is better to die like a man; to die like a sailor in the blue water no man can object. But I am captain, and I must not leave my ship. But I shall baffle this fiend or monster, for I shall tie my hands to the wheel when my strength begins to fail, and along with them I shall tie that which He - it! - dare not touch; and then, come good wind or foul, I shall save my soul, and my honour as a captain.

On the 24th October 1885 the town of Whitby bore witness to an incident that would later become the basis for one of the most famous shipwrecks in the history of literature.

The following extract is taken from an article that appeared in the Whitby Gazette on the 31st October 1885.

A little later in the afternoon a schooner was descried to the south of the harbour, outside the rocks. Her position was one of great danger; for being evidently unable to beat off, there seemed nothing for it but to be driven among the huge breakers on the scar. Her commander was apparently a man well acquainted with his profession, for with consummate skill he steered his trim little craft before the wind, crossing the rocks by what is known as the ’sledway’ and bringing her in a good position for the harbour mouth.

The piers and the cliffs were thronged with expectant people, and the lifeboat ‘Harriot Forteath’ was got ready for use in case the craft should miss the entrance to the harbour and be driven on shore. When a few hundred yards from the piers she was knocked about considerably by the heavy seas, but on crossing the bar the sea calmed a little and she sailed into smooth water. A cheer broke from the spectators on the pier when they saw her in safety.

Two pilots were in waiting, and at once gave instruction to those on board, but meanwhile the captain not realising the necessity of keeping on her steerage, allowed her to fall off and lowered sail, thus causing the vessel to swing towards the sand on the east side of the harbour. On seeing this danger the anchor was dropped, but they found no hold and she drifted into Collier’s Hope and struck the ground. She purported to be the schooner ’Dmitry’ of Narva, Russia, Captain Sikki, with a crew of seven hands, ballasted with silver sand. During the night of Saturday the men worked incessantly upon her that her masts went by the board and on Sunday morning, she lay high and dry a broken and complete wreck, firmly embedded in the sand.

The connection between the Irish author Bram Stoker and Whitby are very well documented, it is also well known that the wrecking of the Russian schooner the ‘Dmitry’ inspired Stoker to create one of the most memorable scenes in Dracula - the arrival of the Count in England.

|

| The wreck of the Dmitry (Frank meadow Sutcliffe) |

…leaping from wave to wave as it rushed as headlong speed, swept the strange schooner before the blast, with all sail set, and gained the safety of the harbour. The search light followed her, and a shudder ran through all who saw her, for lashed to the helm was a corpse, with drooping head, which swung horribly to and fro at each motion of the ship. No other form could be seen on deck at all. A great awe came on all as they realised that the ship, as if by a miracle, had found the harbour, unsteered save by the hand of a dead man! However, all took place more quickly than it takes to write these words. The schooner paused not, but rushed across the harbour, pitched herself on that accumulation of sand and gravel washed by many tides and many storms into the south-east corner of the pier jutting under the East Cliff, known locally as Tate Hill Pier.

|

| The Flag of Distress: The brig Mary and Agnes (Frank Meadow Sutcliffe) |

passage taken from the same Gazette article dated 31st October 1885 illustrates.

In the mean while the lifesaving brigade by a well directed rocket threw a line over the brigantine which now was seen to be the Mary and Agnes, of Scarborough. It seemed a long time before the crew on board fixed the apparatus, but eventually this was done, and the youngest of them, a lad of about fifteen years, was sent ashore in the breeches. In being dragged towards the shore the poor little fellow was struck by many seas and considerably buffeted about. There were, however, many ready and willing among those on shore to rush into the water and bring him to land.

What makes this day’s events all the more dramatic is that both shipwrecks were captured on camera by the famous Victorian photographer Frank Meadow Sutcliffe.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)